EX POSITIO, Fernando Sánchez Castillo

09.09 – 20.11.21

Galería Albarrán Bourdais is pleased to announce Fernando Sánchez Castillo first exhibition at the gallery, EX POSITIO.

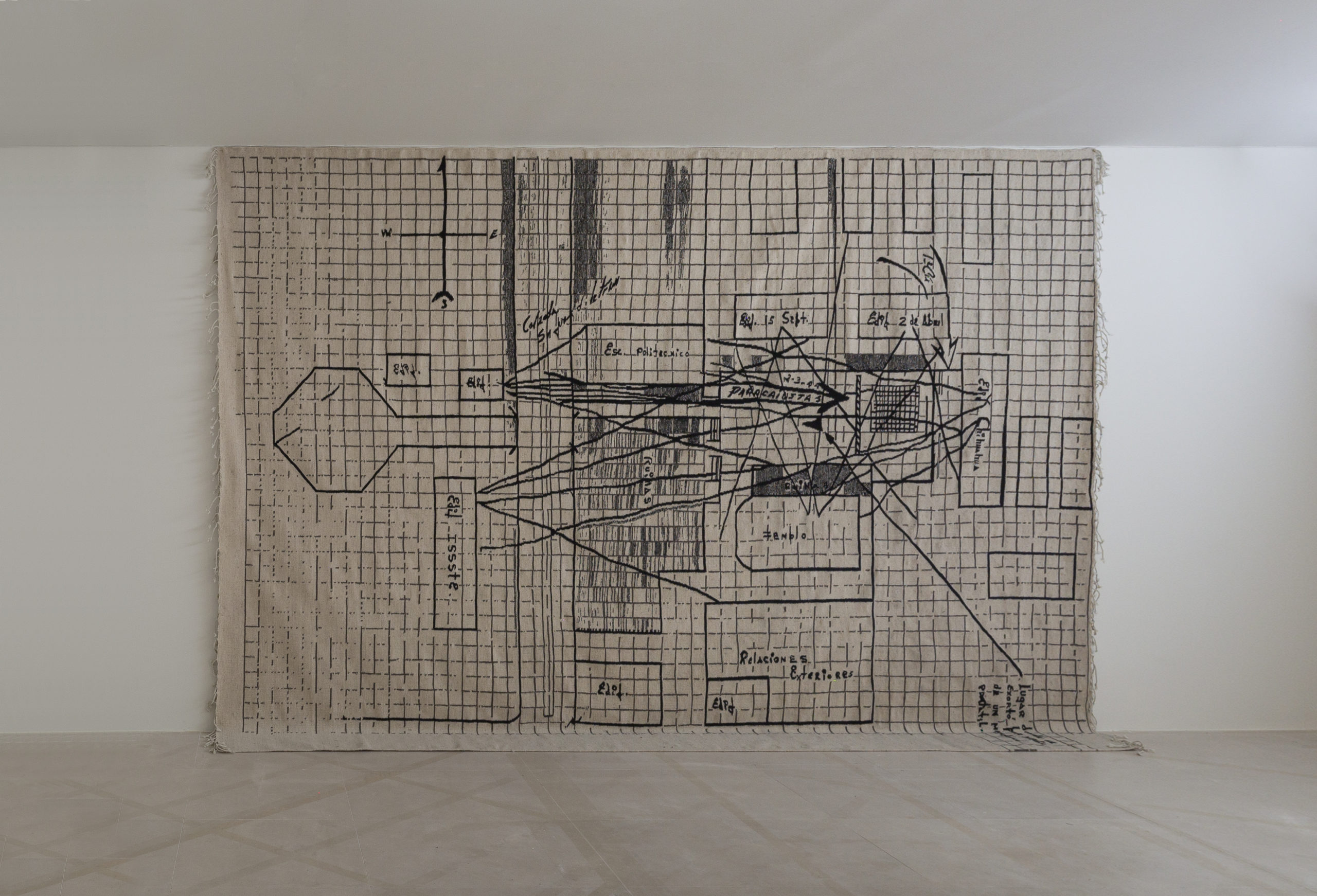

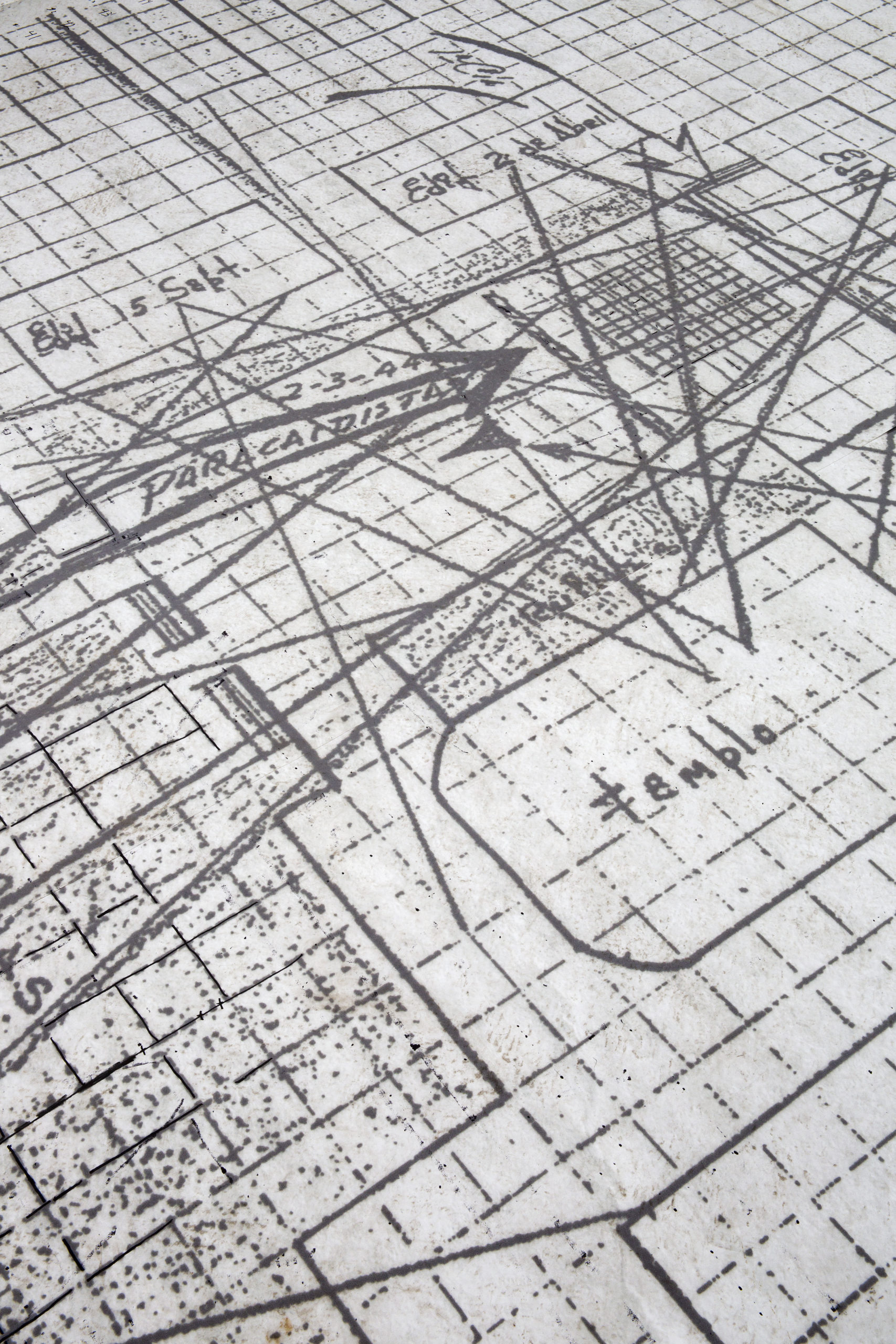

EX POSITIO (To find yourself in a dangerous situation or an abandoned place). In 1968, General García Barragán —in an attempt to clarify what occurred on that fateful night on 2 October 1968, when some 300 students were massacred by his troops— meticulously, and almost compulsively, sketched out how the Olimpia paramilitary snipers were stationed in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, Mexico.

To this day, we still do not know what happened exactly, but General Barragán’s intricate drawing remains, featured in the film El Grito (1), which opens Fernando Sánchez Castillo’s show, EX POSITIO.

The sketch was transmuted into a large monochromatic tapestry and woven, over the course of six months, by a Zapotec artisan at the Sala Siqueiros (2). It is on display alongside the video Amanecer, and —as an act of pseudo-forensics— the artist has positioned cameras to reconstruct the moment when a military helicopter fired two green flares and a single red flare. This is an attack code, known only to a few journalists familiar with the Vietnam War, that signalled the start of the violent Tlatelolco massacre, and became the defining moment when trust in the State was irrevocably broken.

“The revolution is won by fighting, not painting,” asserts Ciro Bustos in a video featured in the exhibition entitled Hasta la verdad siempre, that addresses the State’s loss of credibility. Bustos, a guerrilla fighter and an artist, was the “forced” creator of the drawings the CIA used in its high profile capture of Che Guevara. Always a controversial character and cast off as a scapegoat by all, he arrived at the conclusion that the press and the media are the new battlefields of civil society, instead of the armed struggle to which he dedicated his life. The video features an interview with Sánchez Castillo in which Bustos is shown to be in exile in Malmo, discussing the role of the creator in political shifts and his opinions on the efforts to recover his sketches, which are still in the possession of the US Army.

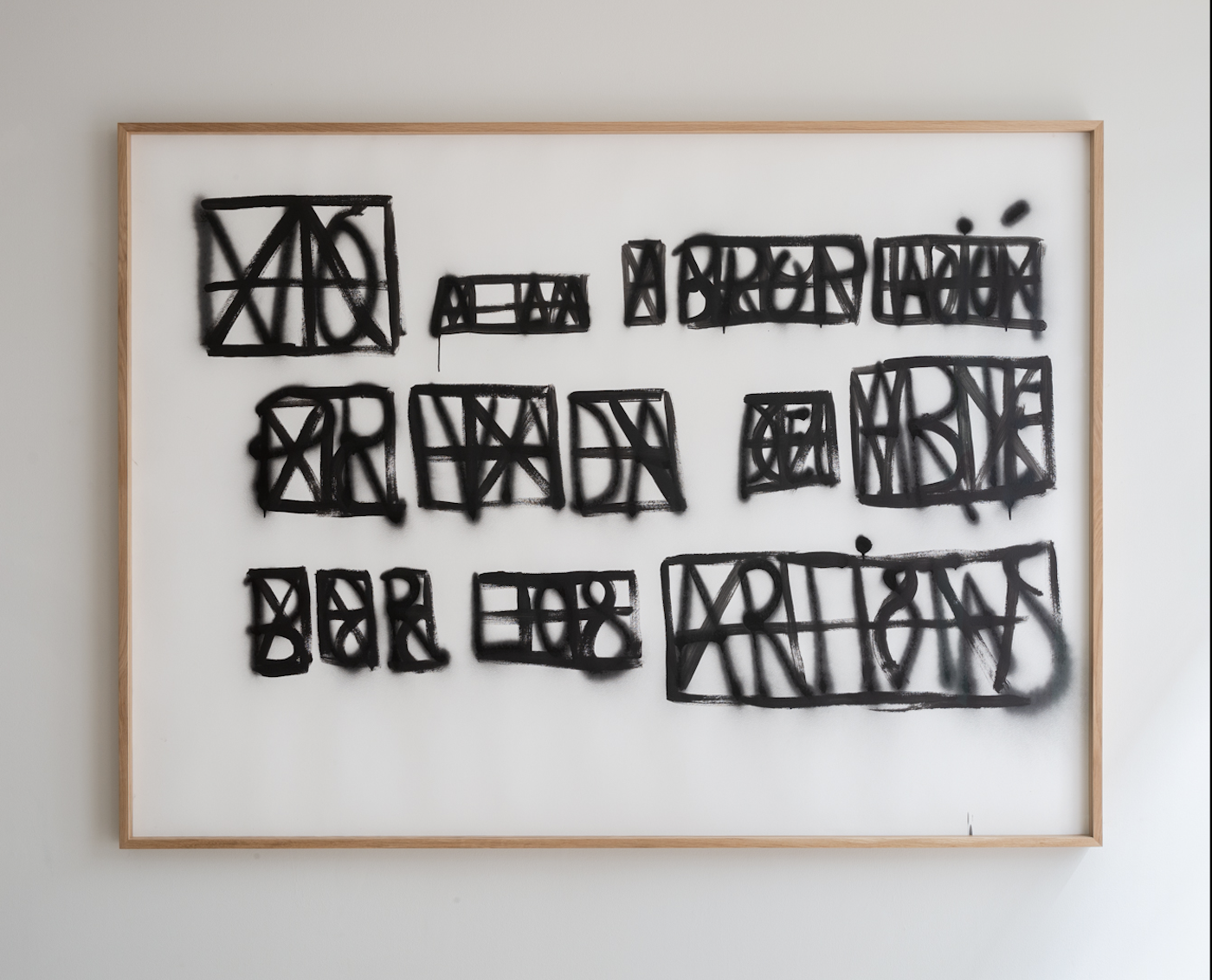

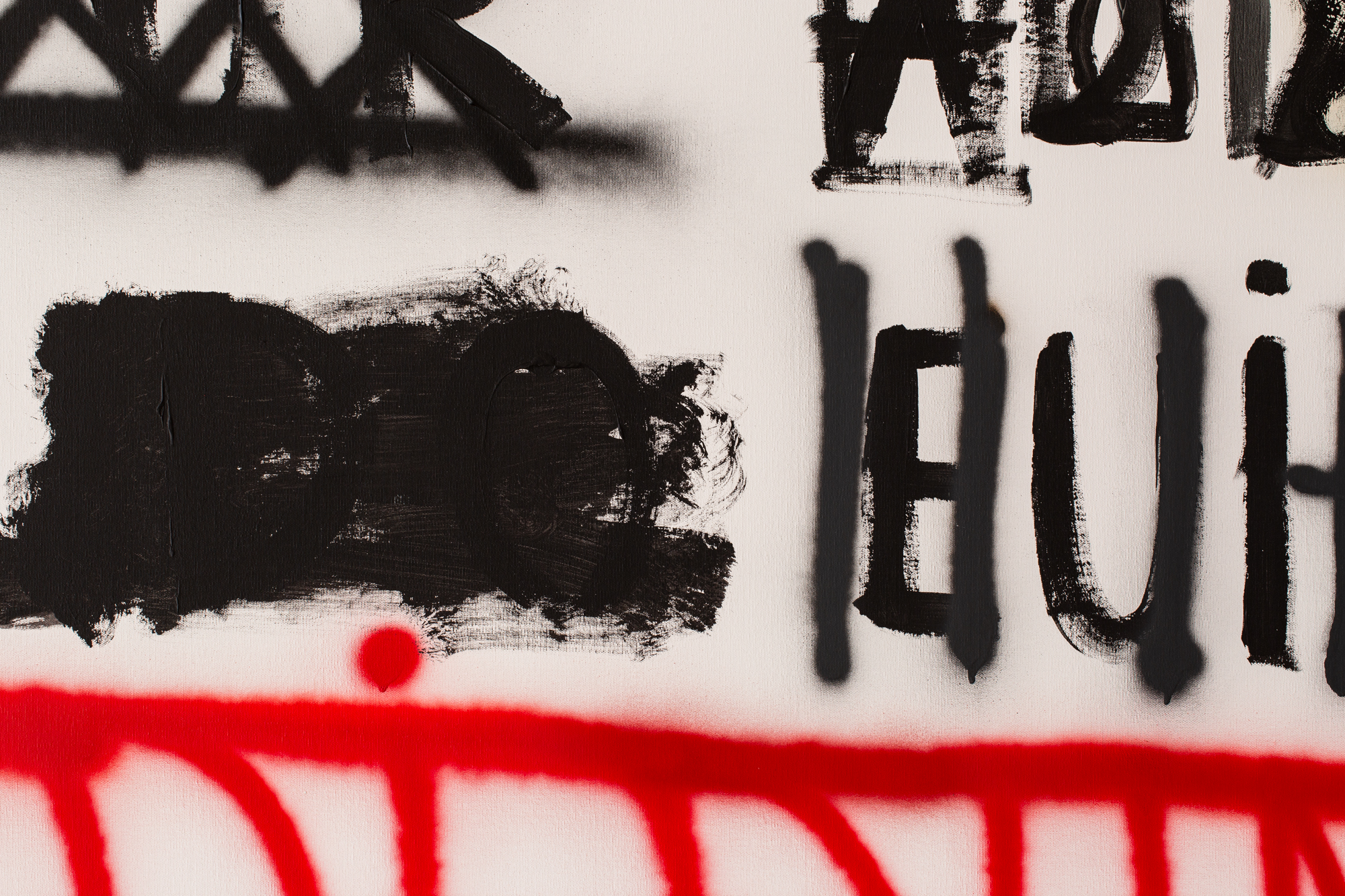

There are other lines and plots, nearly forgotten relics of power struggles, expressed publicly and performatively, that occupy the artist’s attention. Lines and plots obscured by time are the subject of the series Murales. On large paper and canvas, Sánchez Castillo recreates the formal codes of the graffiti that appeared on walls throughout Spain between the death of the dictator Francisco Franco in 1975 and the ratification of the Constitution in 1978. This graffiti, executed by the country’s political and intellectual forces at the time (currently under examination by Germán Labrador and by Pedro Sempere in his day) was covered or obscured on as many as ten different occasions. Each redaction expresses not only obliteration, but something else; they reveal the unique characteristics of the forces that intervened in the social discourse.

New words appeared on the walls of streets and avenues that were refuted in an immediate and expressive way that unveiled the censor, his attitudes, and his opinions. The walls were covered in these palimpsests, through which it was difficult but not impossible to measure the pulse of the social landscape.

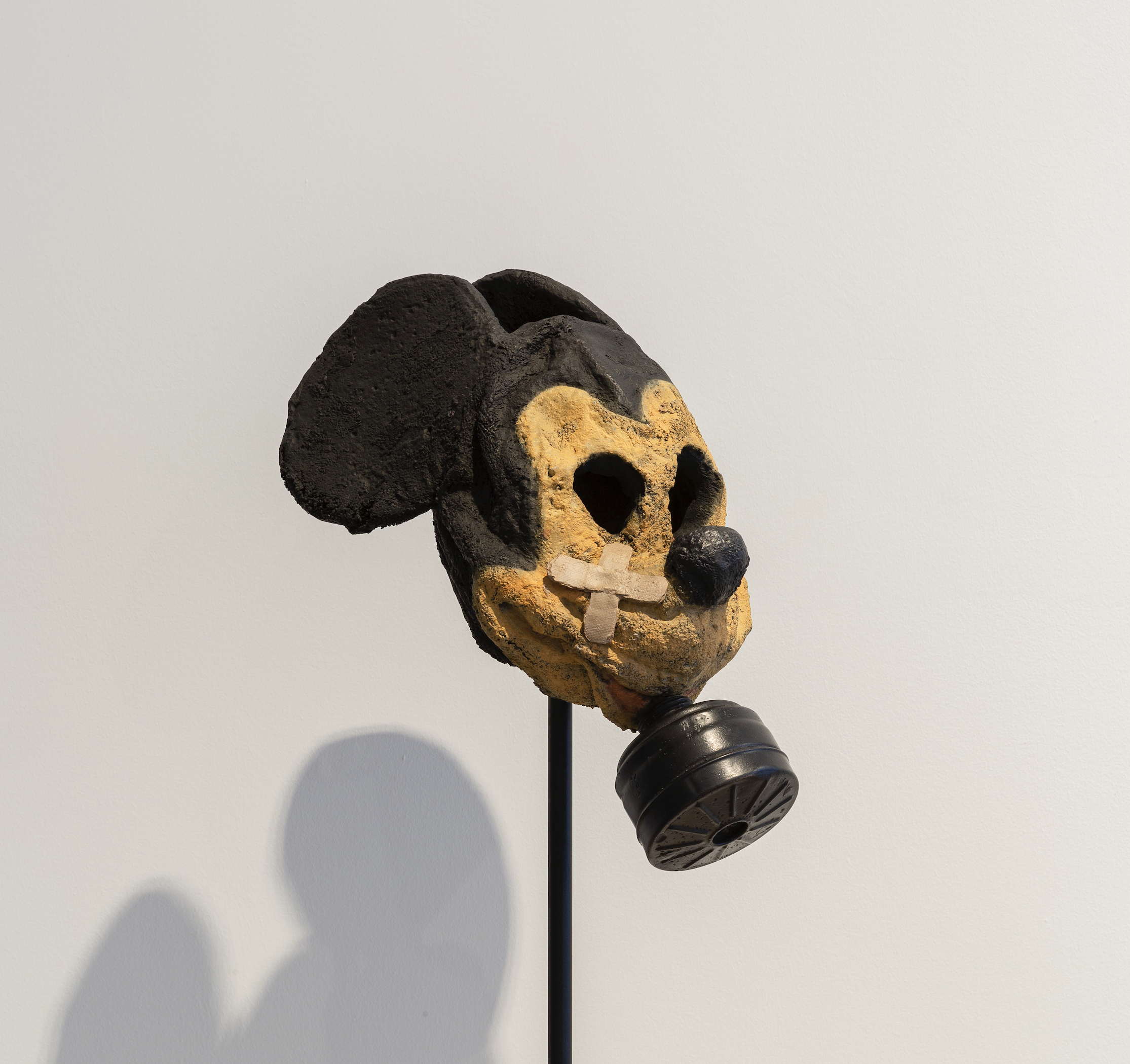

In a semiological continuum, the artist incorporates a series of masks into the exhibition that occupy the liminal space between artistic expression and social demand, created fundamentally to capture the attention of the media and its global, trivial broadcasting; Pussy Riot in bronze, the Bread Man from Cairo, the Tortilla Man in Mexico, and Mickey Mouse from Venezuela blossom in this hybrid soil. The figures infuse the gallery space with protest material in an echo of Rancière’s assertion that the primitive appears from political overflow, as well as in the field of aesthetics.

The protests, graffiti, gestures targeting social networks and dissidence are full of codes yet to be deciphered that we incorporate into desire and social change…

The anecdotal, anonymous, and ephemeral are transferred into the sphere of classical art and memory as a vast anthropological collection to discuss with future generations.

(1) El Grito, Leobardo López Arretche, UNAM, Mexico, 1968.

(2) Ayer fue también un día soleado, Fernando Sánchez Castillo Exhibition, Sala Siqueiros, Polanco, (Mexico City); curated by Gerardo Mosquera, 2018.

Eurídice Arratia / Fernandez Sánchez Castillo