Emergencia

12.09 – 26.10.24

EMERGENCIA

Curated by Marisol Rodríguez

EMERGENCIA, Héctor Zamora’s first solo exhibition at Albarrán Bourdais, presents an unprecedented performance that will take place during Madrid Gallery Weekend, as well as new works from the Poralia series. This series is inspired by the technical and poetic interaction between hyperbolic paraboloids and the upward movement of abyssal fauna. The exhibition serves as a call to attention to the harmonious behaviors that can emerge when a problem affects a community and aims to create a meeting space between the everyday and the extraordinary through three bodies of work that explore the fundamental axes of the Mexican artist’s oeuvre.

Harmony and Destruction

(EMERGENCY is a piece created specifically for the gallery and involves about thirty participants circulating hundreds of vessels, which will be passed hand to hand in a circuit that will see the objects flying through a significant portion of the gallery, entering, exiting, and traversing the space in a way that disrupts the solemnity typically associated with the white cube.)

The logic of circulation is stripped of its productive function in an action that instead explores the tension between harmony and destruction that arises among individuals once the rhythm of exchange is established. This spontaneous choreography that emerges among participants is a key element in Zamora’s work, as the artist seeks a balance between precise calculation (often related to architecture and its structures) and the randomness introduced by human intervention.

Aware of the inevitability of accidents, Zamora introduces colored sand into the vessels. Thus, their fall is welcomed as an opportunity to create a series of ephemeral drawings, which remain on the gallery floor throughout the exhibition. While manipulation and eventual destruction of the artistic object is often taboo in exhibition spaces, in this action, they are the very means of production.

Catalysts, Provocations, Accidents

As early as 2003, Zamora explored the notion of circulation in pieces like *Pneu*, an installation where he created a red plastic cylinder, inflated by a constant air flow that, once activated, traversed the entire multi-story building of the Garash gallery in Mexico City. Like a snake biting its own tail, the piece had neither beginning nor end: it entered through the main door, traversed the space, exited through the back of the building, ascended to the roof, and returned to the entrance in an imposing and impenetrable loop. Since then, the artist has blended ambition with formal economy dictated by the local context of production, using extremely modest means (plastic, fans, a nearly zero budget) to achieve a monumental result that could be interpreted as a challenge to the accessibility, mobility, and hierarchy of the artwork in relation to its viewer.

A decade later, Zamora created the pieces Inconstância Material (2012) and O Abuso da História (2014) in São Paulo, a city where he lived for 9 years and which informed his passion for architecture. In Inconstância Material, Zamora engaged with his interest in brick as a symbol of both an ambivalent triumph of human imagination over its natural environment and manual labor as a pillar of society. The artist’s curiosity about light and even floating structures, as seen in Panamarenko’s work (one could imagine Pneu (2003) as a reverently compressed and joined Aeromodeller (1969-1971)), completed an equation.

If, ten years earlier, a huge red tire imposed itself on the exhibition space, challenging the notion of access, in Inconstância Material, hundreds of bricks created a flow of fired clay animated by construction workers who otherwise would never have set foot in the gallery. The actions generated by the artist create moments of euphoria and freedom, followed by serious and important questions about who and how one can access them.

Two years later, also in São Paulo, Zamora made a symbolic break with the action *O Abuso da História*, where three hundred potted plants were thrown from the balconies of a third floor into the courtyard of an old building. What can this title, referring to historical considerations in an action producing such visceral and immediate effects, signify?

For Ivan Muñiz Reed, Zamora created O Abuso da História in São Paulo in 2014 as an attempt to ‘purge the context’ and create a universal experience with no specific reference to the site. As he often does, the artist combined a few elements to create the work—in this case, the plants and the approximately 20 men who helped throw them. Even in selecting the type of plants, he was careful to avoid any sense of locality; he used the most common signifier of a homogenized experience—a office palm.”

Similar to Roman Signer’s early actions involving throwing or exploding objects, Zamora finds in the act of throwing an emotional catalyst that does not need to be over-explained to reveal its aesthetic and discursive power. The artist avoids indicating any conclusions to the questions these pieces generate, preferring to question some of the social margins that censor, limit, or repress his actions (throwing, blocking, destroying). Thus, balloons, bricks, plants, and vessels circulate, fly, open paths or obstruct them; they crash and become debris, or produce something new when they smash. In Zamora’s work, all these objects come to life and burst into our spaces, provoking, with their presence, spaces of freedom, often joyful, always reflective.

The Geometry of the Jellyfish

Throughout his career, Héctor Zamora has explored specific aspects of geometry and architecture, using terracotta blocks and bricks from Spain, Mexico, or Brazil as raw material. In the compositions he has created with these, the artist seeks to formally exploit all the potentialities of a particular type of brick, based on geometric exercises and set theory to complicate its interpretation, transforming it from a construction unit to an element of language, both rational and spiritual.

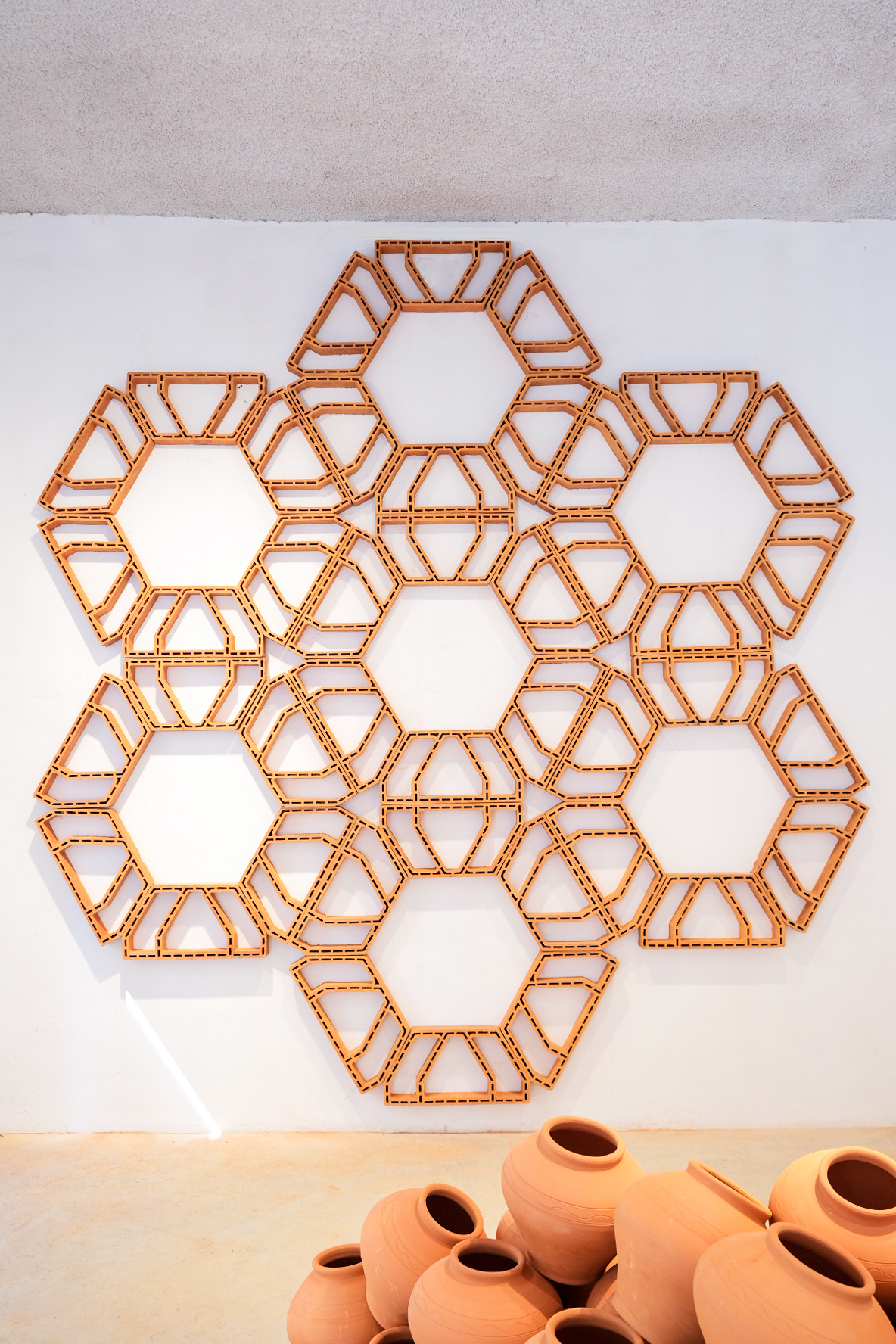

This is the case with the piece L’oeuf de vie (2024), a sculpture that occupies an entire wall of the gallery and in which Zamora transforms a set of industrially produced terracotta bricks into something resembling a flower that seems to vibrate in space.

With its title, L’oeuf de vie (The Egg of Life), Zamora alludes to his observation of what are known as sacred geometries, identified since antiquity in nature (the paradigmatic example being the logarithmic shells of nautiluses) and used, especially in religious architectures and ornaments, as a vehicle for spirituality expressed through mathematics. In the piece, a group of French construction bricks are elevated to a contemplative plane without ceasing to be bricks that mysteriously and harmoniously blend with their environment.

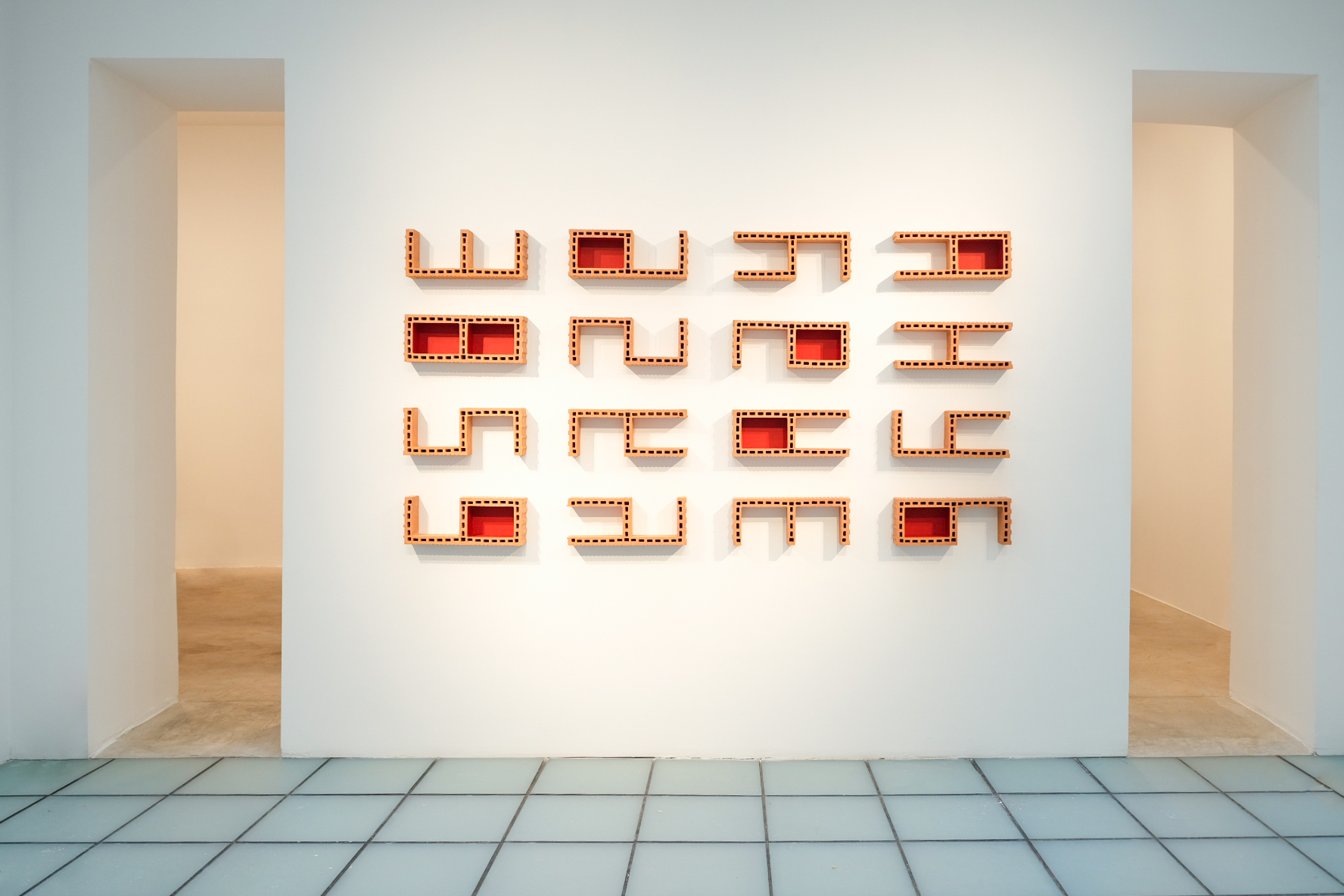

Other formal exercises accompany the ambitious and often ephemeral installations that Héctor Zamora has created worldwide. The pieces ROJO Brique à bancher – acrotère (2024) and Azul 16 Brique à bancher – acrotère (2024) are part of a series that was born simultaneously with Lattice Detour, the monumental intervention Zamora realized on the terrace of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2020.

Inspired by Donald Judd’s work (whose retrospective at MoMA he saw in late 2020) and his quest to find in the balance of material, space, and color the invisible essence of art, Zamora introduces color for the first time into a series of minimalist compositions, recalling with their shapes, colors, and installation protocols Judd’s untitled works created in 1986. In these, a field of color was divided by configurations of vertical lines cut into the negative space of a series of three-dimensional rectangles and parallelograms.

The exhibition culminates with a new series of sculptures where the artist continues the explorations he conducted in pieces like Synclastic/Anticlastic (2009), where concrete structures created from hyperbolic paraboloids resembled a bird or mobula (manta ray) at different moments of flight in its transformation process into a synclastic surface, also architecturally plausible (the earliest structures created with these forms date back to the 2nd century).

In other pieces such as Hypars, intersections series (2014), Zamora was directly inspired by the work of Félix Candela (1910-1997), a Madrid-born architect who was exiled in 1939 to Mexico City, where he made a mark on the architectural landscape with unusual structures, both mathematically complex and sensorially eloquent, rich in generous curves and ascending forms.

In his most recent series, Poralia (2024), Zamora blends lessons from Candela with his interest in the movement of jellyfish of the same name, creatures that elegantly propel themselves through the deep ocean waters. In the installation, the Poralias roam through the gallery space, challenging heights with their glazed ceramic and steel structures.

– Marisol Rodríguez

The exhibition is curated by Marisol Rodríguez (Mexico City, 1984), a writer, editor, and curator focused on the intersec- tion of cultural history, popular culture, and contemporary art. Currently based in Paris, her independent projects include her role as guest curator for the 13th Dakar Biennale under the artistic direction of Simon Njami (2018); the exhibition AMEXICA, featuring works from the Servais Family Collection at the Mexican Cultural Institute in Paris (April-June 2023); and Chromosome Comic, at Biquini Wax EPS in Mexico City (2023).